MS is closely associated with obesity, which has shown a disturbing increase in prevalence, both in the US and worldwide, creating an unprecedented risk for CV disease (CVD). Obesity is prevalent across all demographic groups and is non-gender-specific.Nearly two-thirds of all adult Americans are now considered overweight or obese. Obesity is also rampant in children and adolescents, with 50% of severely obese youngsters meeting MS criteria.

MS is closely associated with obesity, which has shown a disturbing increase in prevalence, both in the US and worldwide, creating an unprecedented risk for CV disease (CVD). Obesity is prevalent across all demographic groups and is non-gender-specific.Nearly two-thirds of all adult Americans are now considered overweight or obese. Obesity is also rampant in children and adolescents, with 50% of severely obese youngsters meeting MS criteria. Pathologic studies have shown that obesity is associated with accelerated atherosclerosis in the young, with traditional risk factors accounting for only 15% of the effect of obesity on atherosclerosis. It is now estimated that the lifetime risk of developing diabetes for children born in 2000 is 33% to 39%.

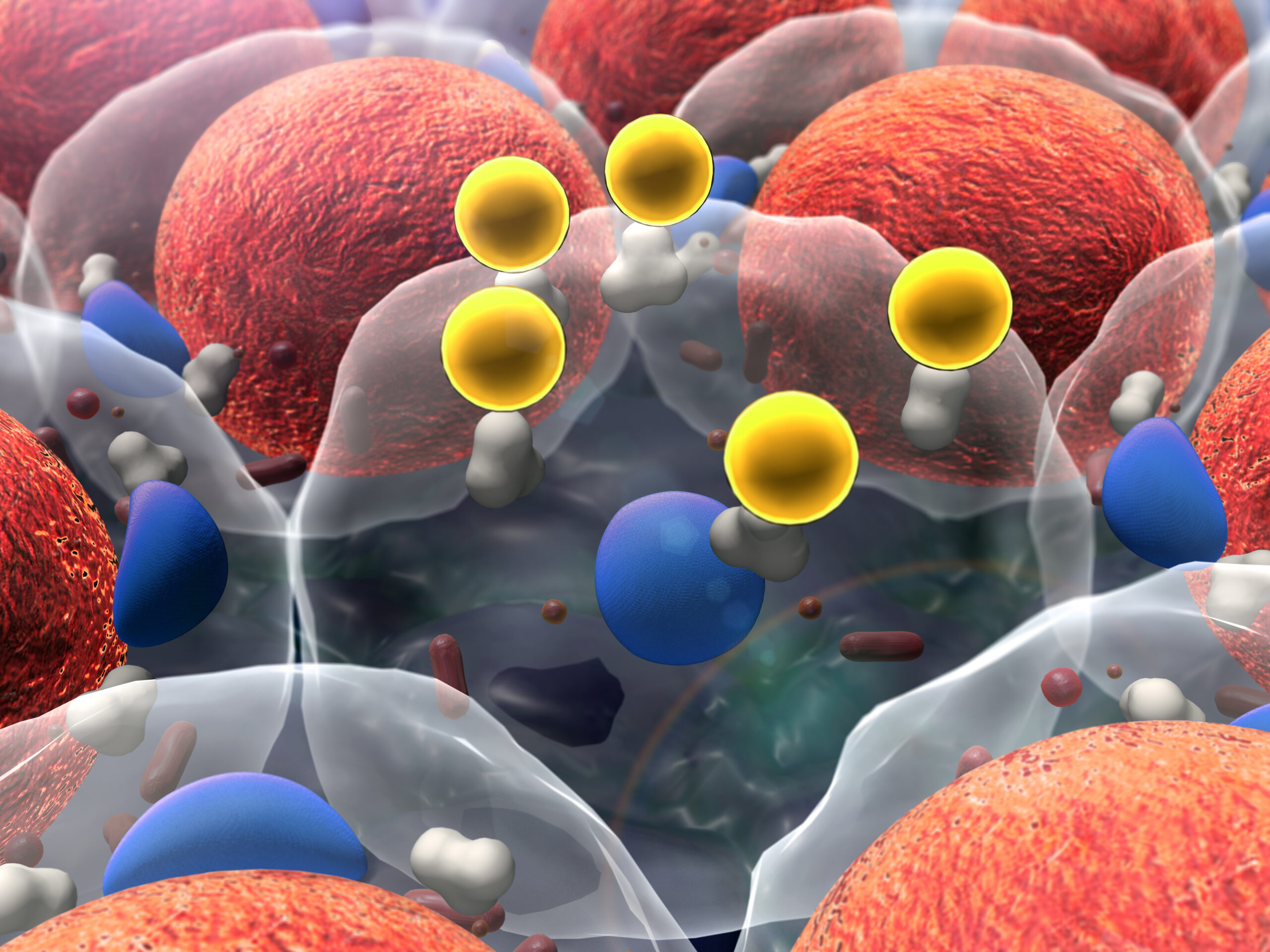

MS increases the risk of CVD, even in the absence of overt diabetes mellitus (DM), with a two- to four-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke in both men and woman.The strongest association with CV events is seen with hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL cholesterol, although HTN and glucose abnormalities are also independent predictors of the prevalence of CVD. Insulin-resistant subjects have lower HDL levels and higher systolic blood pressure and triglyceride levels compared with normal subjects well before they develop diabetes, leading to the ‘tickingclock’ hypothesis. In the Nurse Health Study, women who developed DM during follow-up had a 3.8-fold increase in risk of MI prior to their diagnosis of DM, as well as a 4.6 relative CV risk for the period after the diagnosis of DM. Diabetes is now considered a cardiovascular risk equivalent (meaning that by the time diabetes is diagnosed the patient has likely already established CVD. MS is an even more striking predictor of DM than CV events. Men with multiple features of MS have over a three-fold increased risk of CV events and a 20-fold increased risk of DM. The central components of CV risk in MS are visceral (central) obesity and resultant insulin resistance.Although obesity is a powerful risk factor for DM and CVD, substantial heterogeneity exists in the distribution of fat and the relationship between metabolic disturbances and obesity. A significant minority of obese subjects are not insulin-resistant and, conversely, lean subjects may be insulin-resistant. Adipocytes secrete multiple proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and it is now well appreciated that MS is a proinflammatory condition, leading to increased vascular oxidative stress and the early development of endothelial dysfunction. Adipocytes also secrete and influence the actions of multiple signaling molecules (‘adipokines’), such as leptin, resistin, and adiponectin that contribute to insulin resistance and CV risk. For example, adiponectin levels are inversely correlated with insulin resistance and coronary artery disease (CAD).

It has been estimated that 30% of IL-6 production comes from adipocytes and directly influences the hepatic production of C-reactive protein (CRP). CRP levels vary in direct proportion to the number of metabolic abnormalities. Chronic subclinical inflammation is an important part of MS, as CRP is independently related to obesity, insulin sensitivity, and MS itself. CRP remains a highly significant predictor of both DM and CV events when adjusted for other CV risk factors. In addition to correlating well with all five of the easily measured components of MS, CRP also correlates with insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction, and impaired fibrinolysis. Environmental factors (high caloric density diet and sedentary lifestyle) are also dominant factors in the epidemic of obesity and MS and the search continues to define specific genetic abnormalities associated with MS.

The lipoprotein abnormalities of MS (increased levels of triglycerides and triglyceride rich particles, small dense low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles, with marked reductions in HDL (including HDL-2 particles)) are extremely atherogenic and play an enormous role in the development of CV events.Hypertriglyceridemia leads to low HDL levels and increased sd-LDL particles, primarily due to the activity of cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP).Triglyceride-rich HDL is hydrolyzed by hepatic lipase, and, to a lesser extent, lipoprotein lipase, which generates smaller HDL particles. Small dense HDL particles shed apolipoprotein-A1, which is then catabolized in the kidney. Similarly, VLDL triglyceride is exchanged for LDL cholesterol in the presence of CETP. The hydrolysis of LDL triglyceride generates sd-LDL particles.

To capture the risk of triglyceride remnants, the calculation of non-HDL cholesterol is helpful when triglycerides exceed 200mg/dl. Small dense LDL is associated with a three-fold increased CV risk compared with larger LDL particles. Optimization of glycemic control by insulin and thiazolidinediones (TZDs) improves LDL particle size, as does treatment with niacin. Statins markedly reduce total LDL concentrations, but generally do not alter particle size distribution. Fibrate therapy typically increases particle size, but clinical data is conflicting. Patients with established CVD and multiple risk factors of MS (especially elevated triglycerides, non-HDL cholesterol, and low HDL-C) are considered very high risk; this favors treatment to a lower LDL goal of <70mg/dl.