In young hyperthyroid patients, Graves’ disease is the most likely explanation for the patient’s symptoms; however, there are other reasons that have to be considered. A hyperthyroid metabolic state can also be caused by thyroid cell inflammation and destruction. As thyroid cells die, their stored supplies of thyroid hormone are released into the blood circulation. These bursts of thyroid hormones are responsible for the symptoms of hyperthyroidism. This ‘leakage’ phenomenon has nothing to do with the stimulation of the thyroidstimulating hormone (TSH)-receptor typical of Graves’ disease.

In young hyperthyroid patients, Graves’ disease is the most likely explanation for the patient’s symptoms; however, there are other reasons that have to be considered. A hyperthyroid metabolic state can also be caused by thyroid cell inflammation and destruction. As thyroid cells die, their stored supplies of thyroid hormone are released into the blood circulation. These bursts of thyroid hormones are responsible for the symptoms of hyperthyroidism. This ‘leakage’ phenomenon has nothing to do with the stimulation of the thyroidstimulating hormone (TSH)-receptor typical of Graves’ disease. It can occur in post-partum thyroiditis, ‘silent thyroiditis’, thyroiditis de Quervain and the initial ‘active’ state of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is an autoimmune disease first described by Hakaru Hashimoto in 1912.1 Antibodies against thyroid peroxidase – antithyroid peroxidase antibody (anti-TPO) and/or antithyroglobulin (anti-Tg) – cause a gradual destruction of follicles in the thyroid gland. The diagnosis can be established by measuring these antibodies in the blood. However, a small percentage of patients may have none of these antibodies present. A percentage of the population may also have these antibodies without developing Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Therefore, it is helpful to establish the diagnosis by the typical picture in ultrasonography. The histological picture of the thyroid gland is characterised by an invasion of the thyroid tissue by leukocytes, mainly T lymphocytes. It occurs far more often in women than in men (10–20:1), and is most prevalent between 45 and 65 years of age. The disease is believed to be the most common cause of primary hypothyroidism.

It should be pointed out that, especially in the US literature, the term ‘hashitoxicosis’ is sometimes used to describe an autoimmune thyroid disease overlap syndrome of Graves’ and Hashimoto’s disease.2 In this article the term is strictly limited to the ‘leakage’ symptoms of active Hashimoto’s disease.

Hashitoxicosis is most likely to present in the early stages of autoimmune hypothyroidism. We will describe three cases from our clinic.

In our first case, a 29-year-old male patient, the diagnosis of hyperthyroidism (in his and the following cases with elevated free triiodothyronine 3 [fT3], free thyroxine 4 [fT4] and suppressed TSH) was established in March 2008 due to tachycardia. From a retrospective viewpoint, prodromi such as tremors, petulance and restlessness had occurred two months earlier. The autoantibody profile was anti-Tg 116U/ml (<60), anti-TPO 69U/ml (<60) and TSH-receptordirected immunoassay kit test (TRAK)-negative. Thyroglobin was elevated at 106ng/ml (<1). Thyrostatic therapy had been initiated immediately after the diagnosis of hyperthyroidism and before the autoantibodies were available. Euthyroidism was established after two weeks and the thionamides were withdrawn one week later. As expected, ultrasonography showed only minor hypoechoic areas with normal vascularisation in colour Doppler in relation to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, as the disease was in its initial stage (see Figure 1). The typical signs of Graves’ disease – an enlarged hypoechoic thyroid gland with highly increased vascularisation – could be clearly ruled out. Thyroid hormone replacement therapy has been necessary since May 2008.

The second patient was a 42-year-old female presenting with tachycardia and mood swings who was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism in February 2008. Thyrostatic therapy was initiated immediately after the diagnosis and before the autoantibodies were available. The autoantibody status was anti-Tg antibodies 47U/ml (<60), anti-TPO 137U/ml (<60) and TRAK 1.21U/l (<1.5). Thyroglobulin was elevated at 42.9ng/ml (<1). Due to elevated liver enzymes, thyrostatic therapy was performed for only one month and therapy with beta-blockers was continued. A euthyroid metabolic status was observed in July 2008. At that time, ultrasound showed a normal-sized thyroid with multiple hypoechoic 3–15mm areas and slightly increased vascularisation (see Figure 2).

In October 2007, the third patient, a 41-year-old female, was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism after presenting with tachycardia, mood swings and fatigue. The autoantibody profile was anti-Tg <20U/ml (<60), anti- TPO 518U/ml (<60) and TRAK <1.0U/l (normal<1.5). Thyroglobulin was elevated 89.3ng/ml (<1). After the onset of thyrostatic therapy, she became euthyroid after one month and did not develop hypothyroidism. Interestingly, in this patient the diagnosis of hyperthyroidism was simultaneously accompanied by a diagnosis of Addison’s disease. The adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) test showed cortisol basal 0.5μg/dl 30 minutes after stimulation: 0.6μg/dl (normal>21μg/dl), ACTH 1,036pg/ml (10–60) and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) 55ng/ml (400–2,170). The patient is under steady surveillance for early detection of other features of the autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome.

Discussion

The diagnosis of hashitoxicosis may be complicated, as presenting features sometimes exhibit a significant overlap with Graves’ disease. The autoantibody titres are not always helpful. A review by Saravanan and Dayan3 summarising the immunobiology, assay methodology and prevalence in thyroid diseases of each of the major thyroid autoantibodies provided estimates of the prevalence of such antibodies (see Table 1).

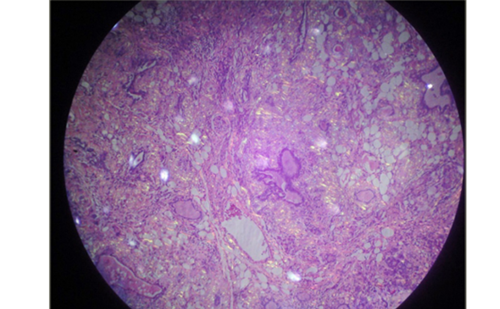

As can be clearly observed in our three cases, ultrasonography is a useful tool in the differential diagnosis between hashitoxicosis and Graves’ disease, as a normal thyroid shows a hyperechoic echotexture with some mild vascularisation (see Figure 3).

The classic sonographic finding of autoimmune thyroiditis is a hypoechoic echo texture of the thyroid. In Hashimoto thyroditis with a normal clinical course, the chronic inflammation leads mostly to atrophy of the thyroid with an indolent thyroid reduced in size, displaying a non-homogeneous hypoechoic texture (see Figure 4).

If Hashimoto thyroiditis is diagnosed at an early stage, the thyroid is a normal size and hypoechoic areas occur in a diffuse pattern. In the hyperthyroid phase of Hashimoto thyroiditis – hashitoxicosis – it is necessary to distinguish this picture from Graves’ disease. The differential diagnosis in ultrasound between hashitoxicosis and Graves’ disease is based on the grade of vascularisation. Whereas Graves’ disease is characterised by highly increased vascularisation in colour Doppler ‘vascular inferno’ (see Figure 5), Hashimoto thyroiditis – even in the initial stage of hyperthyroidismus – shows a normal or only slightly increased vascularisation (see Figure 5). The criteria for the differential diagnosis in ultrasound between hashitoxicosis and Graves’ disease are summarised in Table 2.

Elevated thyroglobin values may be helpful as an indication of the destruction of the thyroid follicles. Thyroid scintigraphy is also likely to be an useful test to distinguish between causes of hyperthyroidism: it will show abnormally increased homogeneous radiotracer uptake throughout the thyroid in Graves’ disease, but not necessarily in hashitoxicosis, where the radiotracer uptake can be expected to be normal or only modestly elevated. However, this investigation is usually not necessary.

Data on the possible incidence of hashitoxicosis are rare and such observations are often published as case reports.4,5 For example, a total of 67 adult patients with chronic autoimmune thyroid disease were followed, mainly as outpatients, for a period of a few months to over 15 years by Modignani et al.6 Episodes of hashitoxicosis were detected in 4.47% of the patients.

Nabhan et al.7 reviewed the medical records of children diagnosed with Hashimoto thyroiditis between 1993 and 2002. Of 69 patient with autoimmune thyroiditis, eight were diagnosed with hashitoxicosis (11.69%). The duration of hyperthyroidism ranged from 31 to 168 days. Three patients became hypothyroid after an average of 46±13.2 days, and five patients became euthyroid after an average of 112.8±59.8 days. Only one of the eight patients had been treated with methimazole; the others were treated with a beta-blocker or not at all.

The authors tried to identify factors predisposing to the development of hashitoxicosis, such as sex, age, family history, thyroid hormone levels, anti-thyroid antibody titres, 123 J thyroid scan results and presenting features. However, no risk factors were identified.

The clinical symptoms of hyperthyroidism are usually described as mild. This was not the case in our patients, and it is also the reason why they had been treated with thionamides before the full set of autoantibodies became available from the laboratory. Given the aetiology of hashitoxicosis, symptomatic treatment – for example with beta-blockers – should be sufficient, as this tends to quickly produce a euthyroid metabolic status.

If the majority of cases with hashitoxicosis really do have a mild course, it can be anticipated that the majority of cases will remain undetected and that valid estimates about the incidence and prevalence of hashitoxicosis are almost impossible to establish.

There are no clear data that its occurrence is a marker for a more rapid progression towards hypothyroidism in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.■