Thyrolipomatosis is a rare condition defined as a diffuse non-neoplastic infiltration of fatty tissue in the thyroid gland.1 Although fatty infiltration is common in other glands (e.g. salivary glands, parathyroids, thymus and pancreas), it is rare in the thyroid gland.2 If present, it is most frequently nodular (i.e. thyrolipoma) rather than diffuse (i.e. thyrolipomatosis).3 Thus, since the first case of thyrolipomatosis was reported in 1942 by Dhayagude,4 only about 30 cases have been published worldwide.5–7 In addition, few of these cases showed concurrency of thyrolipomatosis and malignant neoplasms in the thyroid or colon, but never with tongue cancer. In this report, we present the case of an adult Peruvian patient with squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and incidental thyrolipomatosis, along with a literature review.

Case report

A 44-year-old female patient was assessed at the head and neck surgery outpatient department at a tertiary care public hospital in Lima, Peru, in November 2021. Her main complaint was a tongue mass that had progressively enlarged over the past 1.5 years, which was associated with dysphagia to solids and weight loss. Her history included non-toxic multinodular goitre and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis that were diagnosed when she was in her twenties and treated with leflunomide. There was no history of radiation exposure or any contributing family history. Physical examination revealed a left-sided pearly mass on the tongue (3 cm × 1.5 cm) suggestive of carcinoma, goitre grade IB (i.e. palpable goitre with a painless, mobile, right-sided thyroid nodule), palpable bilateral cervical lymphadenopathies, cervical skin without changes, undernutrition (body mass index 17.8 kg/m2) and vital signs in normal range. Laboratory examinations revealed mild microcytic anaemia (haemoglobin: 11.4 mg/dL; mean corpuscular volume: 73 fL). Cervical ultrasonography revealed a predominantly left-sided multinodular goitre, a left-sided thyroid nodule (31 mm × 22 mm; mixed solid and cystic content; slightly hypoechogenic) and multiple bilateral lymphadenopathies (i.e. a right-side node of 24 mm × 5.9 mm, another right-side node of 12 mm × 4 mm, and a left-sided node of 27 mm × 11 mm). Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the lymph nodes revealed squamous cell carcinoma in the left adenopathy and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia in the right.

The cervical computed tomography (CT) scan with oral contrast staged the squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue as cT3 N2b Mx G1 according to TNM classification (Figure 1). The CT scan also revealed infiltration of the parotids, lymph node conglomerate in the left cervical chain with an infiltrative appearance, and diffuse thyromegaly with multiple septa, cystic content and bilateral fatty infiltration.

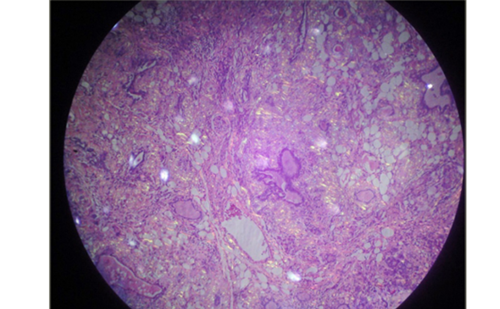

The patient was admitted for surgical intervention that consisted of partial resection of the tongue and thyroid (i.e. left hemiglossectomy and right hemithyroidectomy, respectively) alongside a radical modified cervical lymphadenectomy (type I on the left, type III on the right), and a procedure for mandibular correction (i.e. symphyseal osteotomy). Gross examination of the thyroid specimen (Figure 2) showed a reddish, right thyroid lobule, normal weighted (15 g), increased in size (6 cm × 3.5 cm × 2 cm) of elastic consistency containing colloid cysts and remaining homogeneous parenchyma. Histologic examination of the thyroid specimen (Figure 3) showed non-neoplastic macrofollicular colloidal hyperplasia with cystic degeneration and diffuse fat metaplasia of stromal thyroid tissue, confirmatory of thyrolipomatosis. Biopsy was Congo red negative, excluding amyloid infiltration.

During post-operative follow-up, the patient was euthyroid (thyroid-stimulating hormone 0.733 mU/L). Three months post-operatively, a control cervical ultrasonography suggested metastasis, after images showed a left-sided thyroid nodule with an American College of Radiology Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System score of 4 (18 mm × 13 mm), a left-sided lymphadenopathy (10 mm × 5 mm) and a left cervical mass (43 mm × 26 mm); all of these pathologies had malignant features (e.g. ill-defined borders, heterogenous content and marked Doppler vascularity). Recurrent cancer was confirmed by a FNA cytology of the lymphadenopathy that showed squamous malignant cells. The left neck mass grew rapidly and became painful and bloody (Figure 4). However, as the referred mass was highly vascularized and was located around major vessels (e.g. left carotid artery, subclavian artery and jugular vein, according to angiotomography), the patient was a poor surgical candidate due to high risk of massive bleeding. The multidisciplinary medical team suggested palliative locoregional radiotherapy to reduce mass size and gastrostomy due to dysphagia. Five months post-operatively, the left neck mass became infected; the patient was admitted to hospital and received broad-spectrum antibiotics (meropenem and vancomycin), but septic shock progressed and the patient died.

Discussion

This case report is the first in literature documenting concurrent thyrolipomatosis and squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in an adult Peruvian patient. This presentation suggests that, although thyrolipomatosis is a benign and incidental condition, it may be concurrent with malignant neoplasms.

Table 1 summarizes reported cases and lists the epidemiological features of thyrolipomatosis. For example, there is no predominance by sex (56% male), its occurrence is mostly in middle-aged adults (mean age 51 years; range 44–57 years) and it is usually associated with systemic conditions like chronic kidney failure (39%) and amyloidosis (17%).3,6–21

Thyrolipomatosis is a benign condition because the fatty infiltration of the thyroid gland is diffuse but non-neoplastic. However, some case reports suggest the coexistence of thyrolipomatosis with malignant neoplasms such as papillary thyroid carcinoma or colon cancer.6,22,23 As mentioned, this report is the first published case of a patient with thyrolipomatosis with concurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Table 1 confirms that it may coexist with malignancies in less than 20% of cases.

A hypothesis of causality between thyrolipomatosis and tongue cancer is not reasonable, since these entities have different histopathological findings; nonetheless, the organs in which both conditions are located (i.e. the thyroid and tongue) are embryologically related and may partly explain their coexistence. During the pre-natal period, the thyroid gland arises near the base of the tongue and migrates caudally; it remains attached to the tongue via the thyroglossal duct, which almost always obliterates entirely.24

The underlying pathophysiology of thyrolipomatosis is unclear; it may involve either embryological growth of fatty tissue in the thyroid gland,25 fatty metaplasia of stromal fibroblasts in response to hypoxia14 or a mutation of a mitochondrial protein.25 As thyrolipomatosis causes thyroid swelling, patients usually present with a progressive goitre, either diffuse or nodular, which may be asymptomatic or cause compressive symptoms such as dyspnoea, dysphagia or dysphonia.2,26 Our patient presented with dysphagia due to another condition (a lymphadenopathy). Most patients, as with our case, have normal thyroid function (see Table 1), although some may present with elevated14,27 or decreased 3 thyroid hormone levels.

On work-up, cervical imaging (ultrasonography, CT or magnetic resonance) can suggest adipose thyroid tissue infiltration and is recommended in the pre-operative diagnosis. A CT scan will show an enlarged thyroid gland with areas of fatty attenuation due to lipomatous infiltration intermixed with areas of greater attenuation corresponding to thyroid parenchyma.16,19 Pre-operatively, FNA cytology could also show adipocytes in the thyroid tissue.14,19,28 A definitive diagnosis of thyrolipomatosis is established by histological examination of surgical thyroid specimens after thyroidectomy. Diffuse infiltration of mature adipocytes between sparse thyroid follicles is characteristic,10 as shown in this case.

The differential diagnosis should include other thyroid lesions, both neoplastic and non-neoplastic, that contain mature fatty tissue. Examples of neoplastic lesions include thyrolipoma, papillary carcinoma and follicular carcinoma, while examples of non-neoplastic lesions include an adenomatous nodule, thyrolipomatosis, amyloid goitre, dyshormonogenetic goitre and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.18

Thyrolipoma is the most common fat-containing lesion of the thyroid gland. The characteristic histopathological feature is the presence of mature fatty tissue in the follicular adenoma and a fibrous capsule around the tumour.18 Amyloid goitres are also a relatively common non-neoplastic thyroid lesion that contains fat. The presence of amyloid among non-neoplastic thyroid follicles is characteristic of this condition, and Congo red staining is positive.20,29

Conclusion

Diffuse infiltration of fatty tissue in the thyroid gland is an exceedingly rare, benign and often incidental condition. In the work-up of thyrolipomatosis, concurrent systemic or neoplastic diseases such as tongue cancer could be investigated.