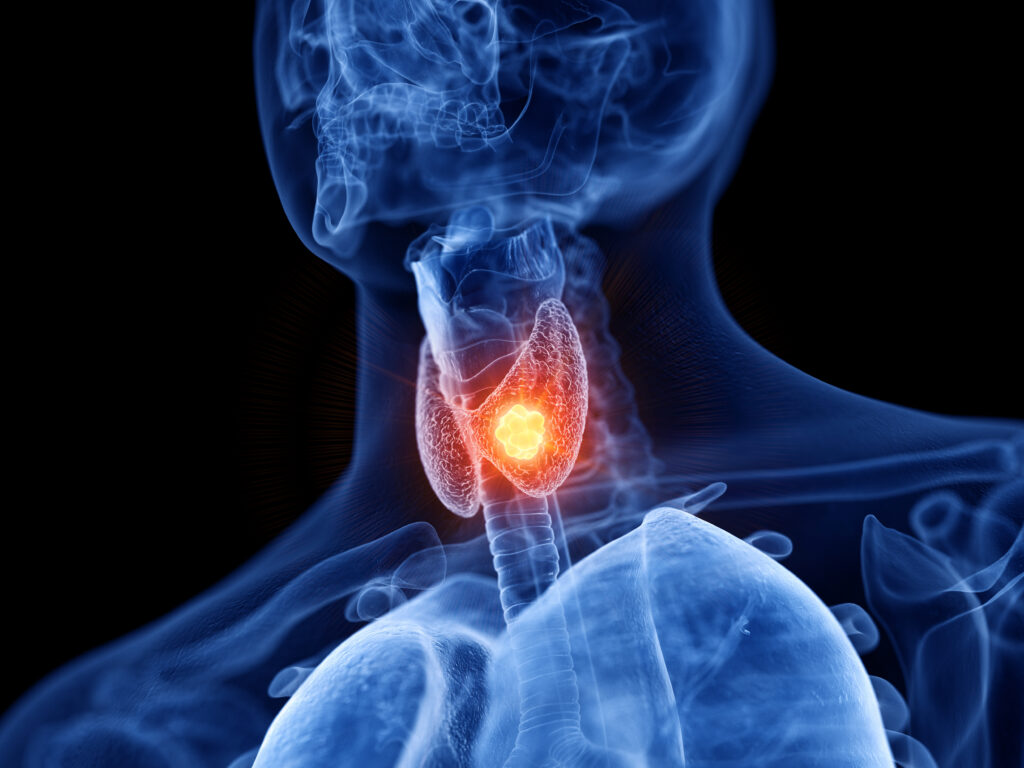

The thyroid gland, located in the front of the neck just below the larynx, secretes hormones that control metabolism. These hormones are thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). Hypothyroidism, also known as an underactive thyroid, occurs when the thyroid gland does not make enough of the thyroid hormones. People with this condition will have symptoms associated with a slow metabolism, including tiredness, constipation and sensitivity to the cold.

The thyroid gland, located in the front of the neck just below the larynx, secretes hormones that control metabolism. These hormones are thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). Hypothyroidism, also known as an underactive thyroid, occurs when the thyroid gland does not make enough of the thyroid hormones. People with this condition will have symptoms associated with a slow metabolism, including tiredness, constipation and sensitivity to the cold.

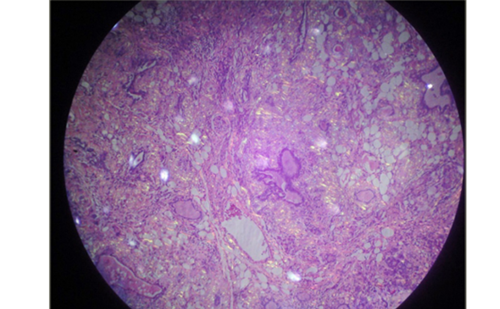

The most common cause of thyroid gland failure is called autoimmune thyroiditis (also known as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis), a form of thyroid inflammation caused by the patient’s own immune system.

Approximately one in 50 women and one in 1,000 men will develop symptoms of hypothyroidism at some stage in their lives. The thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) test, which measures the amount of TSH produced naturally by the pituitary gland, is the most sensitive test of thyroid function.An elevated TSH level almost always indicates an underactive thyroid. Once diagnosed, treatment is usually straightforward, with a synthetic thyroxine called levothyroxine sodium (taken in pill form once a day).The body is able to convert this to T3 just as it would if the thyroid gland were producing the T4 normally. It can take some time to get the dose right.

The vast majority of patients have complete resolution of their symptoms once they are taking thyroxine. However, a small number of patients do not feel entirely normal, even when blood TSH test results come back normal. Doctors find it hard to pinpoint why this would be, and it continues to be the subject of active research.

Currently, T4 is prescribed for hypothyroidism, but earlier practice was to prescribe a combination of T3 and T4, either as desiccated thyroid or combined synthetic T4 and T3. This began to be phased out in the 1970s when scientists learned that 80% of circulating T3 is derived from T4. However, a 1999 study suggested that, for patients whose symptoms do not all improve with T4 therapy, the addition of T3 might be beneficial. However, these results have not been able to be replicated in more recent studies. It is theoretically possible that the addition of T3 to standard T4 treatment still may be of benefit.

Currently, T3 is only available as a short-acting formulation with a relatively brief serum half-life. It is possible that a longer acting preparation might provide a more physiologic way of supplying T3, and thereby be therapeutically useful to certain patients.

The majority (80%) of individuals with hypothyroidism suffer from mild or ‘subclinical’ hypothyroidism. This condition is defined by normal serum levels of free thyroxine with elevated serum TSH levels, typically below 20mU/L.The prevalence in the general population is 5–8%, with a higher prevalence in older women, reaching 15–20% in some studies. It is usually asymptomatic, and often detected by general health screening.

The topic of subclinical hypothyroidism has been the focus of much research and debate. One of the more controversial issues is whether patients with subclinical hypothyroidism should receive thyroxine therapy. Doctors vary in their approach. Some prefer to offer treatment while others recommend frequent monitoring to see whether overt hypothyroidism (defined by free T4 levels below the lower limit of normal) develops.

The reason that therapy of this common condition is so controversial is that there have been very few randomized controlled trials showing benefit from levothyroxine therapy. While some studies have shown that patients with subclinical hypothyroidism have mildly elevated serum lipids, others have not. And while some prospective randomized studies have shown that lipid levels may be lowered with thyroid hormone treatment, this has only been the case when serum TSH levels are >12mU/l, whereas the majority of patients have serum TSH levels <10mU/l. The relationship of subclinical hypothyroidism and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease has been difficult to prove.

Indeed, a recent study of a large cohort of elderly people with subclinical hypothyroidism found no excess risk of heart disease or mortality over an 11-year follow-up period. Similarly, studies showing improvement in symptoms with T4 therapy have generally only been able to document benefit in patients with higher serum TSH levels, indicating more severe degrees of hypothyroidism.

One situation is less controversial: most experts agree that subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnant women should be treated because of possible decreases in IQ of the offspring of untreated women with hypothyroidism. Similarly, women with infertility and subclinical hypothyroidism should also be treated because of small studies suggesting that fertility may be restored with normalization of thyroid function. In addition, some physicians believe that therapy is indicated in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism who have positive anti-thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody titers. These individuals have a higher rate of progression to overt hypothyroidism (approximately 5% per year) than do antibody-negative patients.

On the other hand, arguments against treatment include the fact that most published evidence does not show direct benefit in terms of lipid levels, cardiovascular disease prevention, or improvement in symptoms. In addition, there is the added expense of the medication, the possibility of over-treatment causing iatrogenic hyperthyroidism, and also the recently described spontaneous recovery of normal thyroid function in approximately 50% of patients with subclinical hypothyroidism and negative anti-thyroid antibody titers.

Although some professional societies recommend screening for hypothyroidism based on a perceived benefit of disease detection and treatment, other groups do not recommend routine population screening. For example, the American Thyroid Association recommends screening women over the age of 35 with serum TSH levels every five years, whereas neither the Institute of Medicine nor the US Preventative Services Task Force recommend routine screening.

However, the situation is different in the case of women who are pregnant or who want to become pregnant. Some studies suggest that even very mild hypothyroidism could potentially have detrimental cognitive effects on the offspring.

Thyroid hormone secretion normally increases during early pregnancy. During the first trimester, the fetus is dependent on maternal thyroid hormone for normal brain development. In women with mild hypothyroidism, thyroid hormone levels may not increase to the extent that they should, resulting in possible fetal thyroid hormone deficiency. For this reason, many experts recommend screening to detect mild hypothyroidism either early in pregnancy or even before conception.

An exciting recent study also suggests that euthyroid women with positive anti-TPO antibodies and normal serum TSH levels, who are known to be at risk for miscarriage, have a miscarriage rate no different from control women when treated with thyroid hormone. This suggests that screening with anti-TPO antibodies, and not just serum TSH, might also be indicated in early pregnancy.

Another issue in pregnancy relates to postpartum thyroid disease. Approximately 10% of all women have positive anti-TPO antibodies. Approximately 50% of these women (or 5% of all women) develop postpartum thyroiditis, which can cause both hyper-and hypothyroidism in the postpartum period.

Anticipation of this problem in the postpartum period may be an additional reason to recommend screening with anti-TPO antibodies early in pregnancy. Other groups that might benefit from screening include those with other autoimmune diseases, including type 1 diabetes, as well as those with a positive family history of thyroid disease.

While screening the general population for hypothyroidism may not be justified, there is clearly a case for selective screening or ‘case finding’ in certain high-risk groups. ■