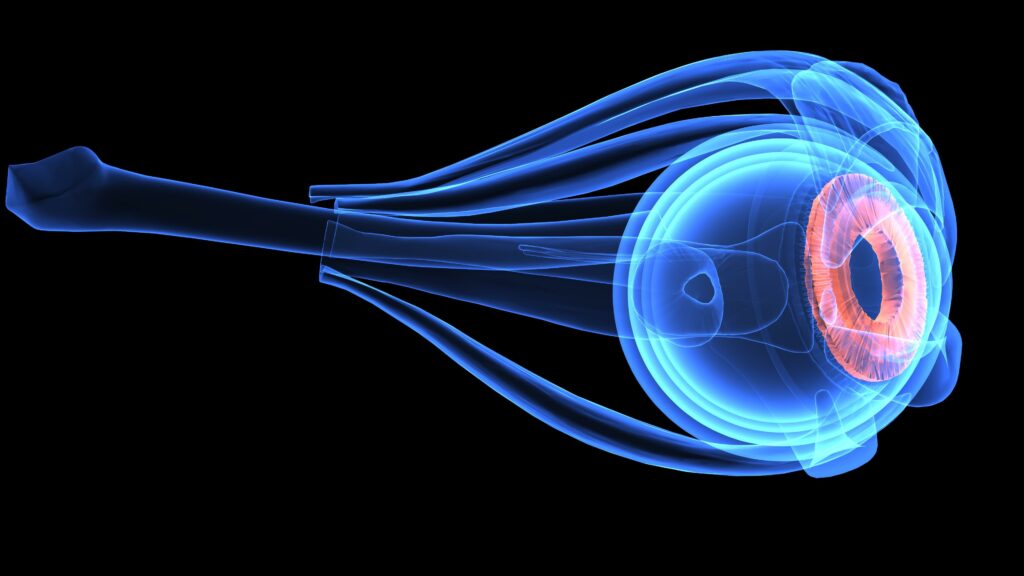

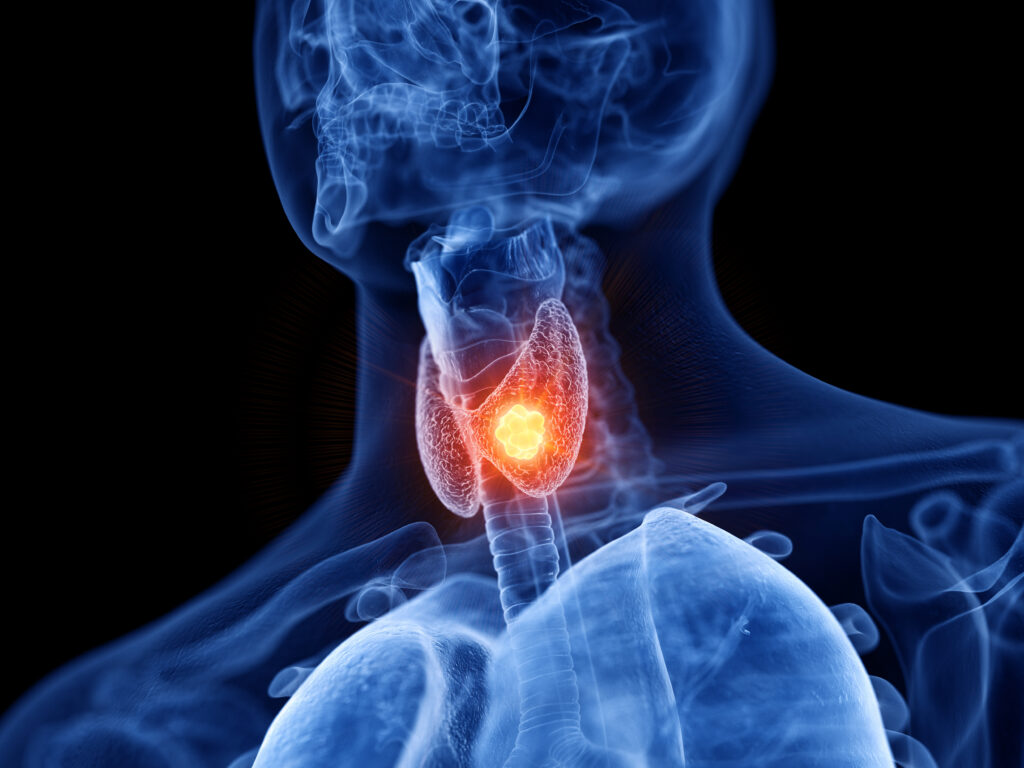

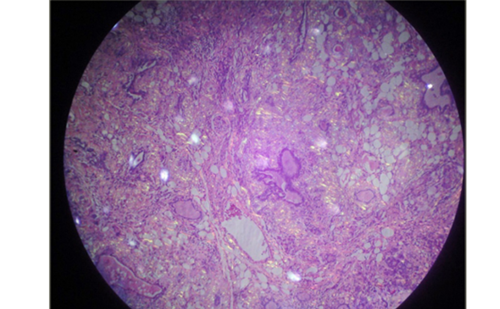

Case presentation A 32-year-old woman presented to our clinic while three months pregnant, with a left-sided neck mass that she had felt about 10 months prior to presentation. She noticed that the mass had grown slightly over that period. She denied symptoms of dysphonia, dyspnea, and dysphagia. A neck ultrasound showed an absent right thyroid lobe and isthmus, along with several left thyroid nodules, with the largest being 4.3 cm and left lateral malignant appearing adenopathy (largest 3.6 cm). Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the left lateral lymph node was consistent with papillary thyroid carcinoma. The patient had normal thyroid function tests. During her 20th week of pregnancy, the patient underwent a left hemithyroidectomy, left central neck dissection and left lateral neck dissection including levels II–IV. Pathology revealed multifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma with largest focus at 5.2 cm with extensive vascular invasion and focal extrathyroidal extension. Five out of 12 lymph nodes were malignant (one in central neck and four in left lateral neck). After delivery of a healthy baby, the patient continued to have detectable thyroglobulin (Tg) at 11.5 ng/ml (Immulite 2000 XPi Thyroglobulin assay, Siemens Inc., Deerfield, IL, which has a functional sensitivity of 0.9 ng/mL) with undetectable anti-Tg antibodies with a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 0.156 uIU/ml and ultrasound examination noted a left level II malignant-appearing lymph node. Neck computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed that and that no other suspicious nodes were present, however, it indicated the presence of a lingual thyroid (see Figure 1). The patient did not want to have re-operation or other additional intervention at that time, and she became pregnant again. After delivery and throughout the following year, she continued to have detectable Tg levels at 89.1 ng/ml with TSH of 9.3 uIU/ml, then 16.4 ng/ml with TSH of 0.075 uIU/ml and then 72 ng/ml with TSH of 86 uIU/ml (all these Tg levels were done using the assay mentioned above). A year after she delivered, she agreed to have re-operation that included left lateral neck dissection along with removal of a benign lingual thyroid (see Figure 2). The patient did not agree to receive radioactive iodine treatment. Her most recent thyroglobulin level was done one month after this last surgery and it was at 2.3 ng/ml (this time the Tg assay was changed to Beckman Access Tg, Beckman Coulter, and was performed at Mayo Clinic Laboratories, Rochester, MN, US, with a functional sensitivity at 0.1 ng/ml) with undetectable anti-Tg antibodies with TSH of 0.09.

Discussion Ectopic thyroid tissue is a rare thyroid developmental abnormality. It is reported to have an incidence of 1 in 5,727 and it is more common in females.1 The majority of these patients are asymptomatic; however, some may have obstructive symptoms.2,3 Hypothyroidism was present in 62% of patients with lingual thyroid in one series,4 while hyperthyroidism is rare.4,5 Thyroid cancer arising in ectopic thyroid tissue is extremely rare at less than 1%.6

Thyroid hemiagenesis (TH) is another rare developmental abnormality with a prevalence as high as 0.2% when determined by ultrasound screening.7 TH is more common in females and left lobe hemiagenesis comprises more than 80% of cases. TH is commonly associated with functional and morphological thyroid disorders.8

Thyroid cancer is rarely seen in patients with TH. In a review of the literature, associated thyroid cancer was only reported in 3% of cases of TH.9 TH was also reported to be associated with ectopic thyroid tissue at a similar rate of about 3%.9 The combination of TH (especially right lobe hemiagenesis), ectopic thyroid tissue and thyroid cancer therefore is

even more uncommon. Huang et al.10 described a case of right thyroid hemiagenesis, prelaryngeal ectopic thyroid and thyroid cancer. We report here an additional case of such combination, where the ectopic thyroid tissue was a lingual thyroid.

A key finding in this case is that thyroid cancer was discovered as a metastatic cervical node and the patient was pregnant. Additional imaging before surgery was limited to neck ultrasound, due to pregnancy. The patient was only noted to have lingual thyroid as she continued to have persistent disease after initial surgery and was found to additional cervical nodal disease where further imaging was performed with a CT scan that indicated the presence of lingual thyroid. In the absence of persistent cervical nodal disease, an elevated thyroglobulin in that setting should also alert the physician to check for ectopic thyroid tissue in the setting of TH.

Conclusion We report a patient who had the extremely rare association between right TH, thyroid cancer in left lobe and lingual thyroid where lingual thyroid was discovered after the initial surgery for thyroid cancer. While this association is rare, it is very important when evaluating a patient with TH and thyroid cancer to consider the possibility of the presence of an ectopic thyroid tissue, as this may alter the surgical approach to include the removal of this ectopic thyroid tissue and also may provide an additional source of persistently detectable thyroglobulin after thyroid cancer surgery.