The year 2016 has been an exciting one in the world of thyroid disease, marking a new era for both research and clinical management. As a subspecialty, we are continuously re-evaluating not only our current treatment strategies, but also our classification of disease, right down to adjusting the nomenclature. All of this has occurred within the last year and the impact of many of these changes is requiring clinical endocrinologists to make significant changes in their approach to patient care. Here, we summarize some of the advancements that have clinical relevance.

Not surprisingly, in 2016 the majority of the literature explored thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer.1 We began the year with the publication of the latest American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer.2 In agreement with the review by Kim et al.,3 at the heart of these new guidelines is the indication that we should be doing much less in management and treatment, but with under the premise that patients are thoroughly and appropriately assessed.

Highlighting this approach are the recommendations to hold the standard for diagnostic fine needle aspiration (FNA) to the most detailed sonographic characteristics of these nodules, eliminating the >5 mm threshold to FNA for high-risk individuals and suggesting that observing sonographically very low risk nodules without FNA is also a reasonable option, no matter how large the lesion. Although highly suspicious thyroid nodules with a benign cytology should have a repeat FNA within a year, it is now recommended that in very low suspicion nodules we should consider discontinuing surveillance altogether after two benign FNA results.

These guidelines have also, at last, added the recommendation of thyroid lobectomy for low-risk thyroid cancer patients with tumors of 1–4 cm in size and strongly recommend lobectomy for sub centimeter thyroid nodules, which can also be closely monitored without surgery as an alternative. Last, but not least, the threshold for administering radioactive iodine (RAI) has been increased significantly, and the routine use of recombinant human thyroid stimulating hormone stimulated thyroglobulin levels has been discouraged in low-risk situations.

So, are these guidelines an advancement? The authors should be congratulated for another monumental task and excellent review of the current thyroid nodule and cancer literature. They certainly correct some points from the previous version, but they appear to some of us to err too much on the side of doing nothing. Discontinuing surveillance of nodular thyroids and just providing surveillance for small thyroid cancers remain controversial suggestions. Of course, if only everyone would stop doing FNAs on small nodules then this situation would not need to be discussed. But as long as fee-for-service in the US continues, we can be sure that such patients will continue to present for advice on future management.

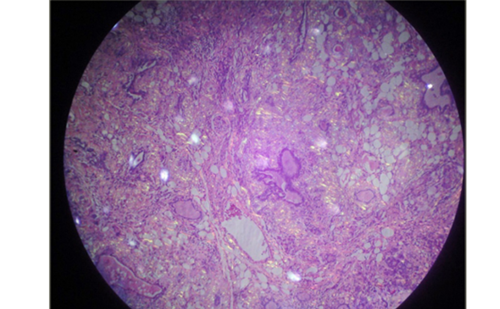

Also this year, there have been multiple articles suggesting a nomenclature revision for encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, which have reached major news media.4 The recommended name for this pathology is now “noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillarylike nuclear features” (NIFTP).5–8 Note the removal of the term ‘carcinoma’. This was a result of an extensive consensus review of a multitude of patients who have had prolonged follow-up after lobectomies with no RAI. They had a recurrence rate of <1%. It is estimated that this new classification may impact >45,000 patients per year worldwide, and will lead to less extensive surgery and a further decrease in RAI use.

Lenvatinib, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), which was approved by both the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency in 2015 for the treatment progressive, radioiodine refractory differentiated thyroid cancer, was definitely in the spotlight this year, with continued positive reports of increased progression-free survival (PFS) rates showing it to be the most promising salvage therapy available for use even in patients who have been treated with another TKI previously.9–11 Nevertheless, an increased long-term survival rate has yet to be demonstrated and the drug side effects can be unpleasant.

A systematic review and meta-analysis on the safety and efficacy of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and ethanol ablation (EA) for treating local recurrence of thyroid cancer,12 showed significant reductions in serum thyroglobulin levels and low complication rates, suggesting this modality may be an alternative to surgical re-intervention. Previous cases using these approaches with benign nodules and cysts have been reported, with some success13,14 but their use in malignant disease may be most useful when surgery is not a good option. A similar approach has been used for parathyroid lesions.15

The debate on subclinical hypothyroidism and pregnancy continues, with over 30 articles published on the subject in 2016. This year, some fairly strong prospective data indicated that subclinical hypothyroidism is not associated with fecundity, pregnancy loss or fewer live births,16 yet there were other reports signaling adverse pregnancy outcomes.17–19 Although a retrospective study suggested that treatment may be of benefit,20 we do not yet have a definitive answer from a large randomized trial. Of note, a study looking at euthyroid women with positive thyroid antibodies found no difference in the rate of miscarriage when treated with levothyroxine.21

In line with last year’s meta-analysis of immunosuppressive monotherapy for Graves’ orbitopathy,22 a meta-analysis looking at the reduction in the relapse rate of Graves’ Disease with immunosuppressive treatment in addition to standard antithyroid therapy was published this year.23 This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on this endpoint, and although the studies reviewed were small, results were very positive favoring immunosuppressive therapy, which may be a promising treatment option in the near future. The surprisingly good results from the use of CellCept in Graves’ orbitopathy24 are exciting but need further confirmation.

In addition, the American Thyroid Association developed new guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis this year.25 In contrast to the thyroid nodule and differentiated thyroid cancer guidelines, however, few changes have been made. Noteworthy are the recommendations to treat postoperative hypocalcemia empirically and/or prophylactically in high-risk Graves’ disease patients undergoing total thyroidectomy, the official institution of the Burch-Wartofsky Point Scale and Japanese Thyroid Association categories for thyroid storm management, instituting thyroid sonography as a standard preoperative test in patients undergoing lobectomy for Toxic Adenoma, and a timing adjustment in the surveillance of thyrotropin receptor autoantibodies during pregnancy.

Finally, the treatment of pregnant patients who have Graves’ disease has continued to be surrounded by controversy. It is clear that methimazole is associated with a rare embryopathy but recent information also indicates that PTU is associated with congenital abnormalities, although of less severity.26 Therefore, it is best to avoid antithyroid drugs as much as possible in women who are planning pregnancy since it is likely they will not come to attention until they are eight weeks pregnant and have already passed the most vulnerable stage of fetal development. Resisting the urge to prescribe such drugs to only mildly hyperthyroid pregnant women would seem the most sensible approach, letting the immunosuppression of pregnancy take over.27