The autoimmune thyroid diseases (AITD) comprise a series of interrelated conditions including Graves’ disease (GD) and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT). AITD are the most prevalent diseases of the thyroid gland in the pediatric population, particularly in adolescence.1

HT is the leading cause of goiter and hypothyroidism in children and adolescents in countries with adequate iodine supplementation.2–3 In an American population aged between 11 and 18 years, five new cases were detected out of 1,000 adolescents screened every year.4 It is a much more common condition in females than in males: 4:1 to 8:1 depending on the geographic region.4–6

In the last decade, discoveries in molecular biology field have allowed new insight into the genes involved in the development of AITD. At least six susceptibility genes whose variants have been associated with AITD were identified: HLA-DR, CD40, CTLA-4, PTPN22, thyroglobulin (Tg), and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor.7 Genetic susceptibility accounts for 70 % risk for disease that, once combined with environmental factors,

play a crucial role in the initiation and progression of the disease.8 Studies with immunoglobulin (Ig)-G4 autoantibody levels in juvenile thyroid disease patients showed evidence of heritability.9

Etiology

HT etiology is multifactorial. The susceptibility to the disease is determined by an interaction between genetic, environmental, and endogenous factors.10,11 Genetic susceptibility is well evidenced by studies of monozygotic and dizygotic twins where the concordance rate for HT is around 38 % for monozygotic and 0 % for dizygotic twins.12 Although genetic factors play a crucial role in the development of HT, nongenetic factors (environmental) are also involved. In immigrant populations from countries with a low incidence of diseases, this population adopts the new country’s incidence rate.13

Strong evidence suggests iodine as the most significant environmental factor in the generation of thyroiditis. In fact, the prevalence of AITD increase in certain geographical regions, such as Japan and the US, and correlates with iodine intake.14 The concentration of iodine in the thyroid

is about 20 to 40 times higher than in the blood, since this element is essential to the synthesis of thyroid hormones. The process consists of the incorporation of iodine into tyrosine residues of Tg, leading to formation of derivatives of mono- and di-iodotyrosine, which subsequently undergo oxidation resulting in the production of the hormones T3 and T4.15 Several studies suggest that the Tg iodization is crucial for recognition by the T cells and, on the other hand, the excess of iodine may affect the Tg molecule directly, by creating new epitopes or exposing cryptic epitopes.16

Pathogenesis

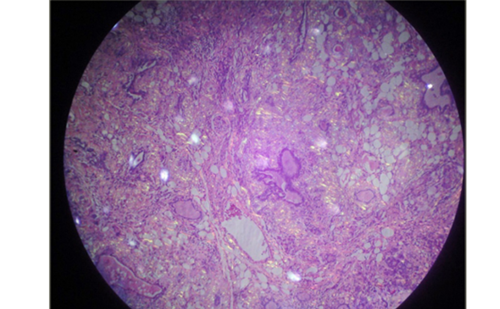

In the original description in 1912, Hashimoto described the histopathologic features of four thyroids with increased volume and a set of common histologic changes. These histologic changes included fibrosis, increasing number of oxyphilic cells (Hürthle), and diffuse lymphocytic infiltration, in which lymphocytes were organized in true lymphoid follicles with germinal centers, designating these changes as lymphoid transformation of thyroid or “goiter linfoadenomatoso.”17

There is no evidence that the ethiopathogenic mechanisms of HT in children and adolescents differs from those activated in adulthood. The currently accepted mechanism of pathogenesis of HT involves three stages. In the early phase, antigen presenting cells (APC), mainly dendritic cells and macrophages, infiltrate the thyroid gland (for details see Figure 1) The infiltration may be induced by an environmental factor (iodine, toxins, infectious agent), which causes cell damage and the exposure of thyrocytes specific proteins. These proteins serve as their own source of antigenic peptides that are presented on the cell surface of APC after processing. Thyroid APC migrate to the lymph node where interactions occur between the APC cells, activated T cells, and B cells, leading to the induction of a variety of autoantibodies against thyroid-specific antigens.

In the next step, B lymphocytes, cytotoxic T cells, and macrophages infiltrate the thyroid. In this phase there is a clonal expansion of lymphocytes and propagation of lymphoid tissue in the thyroid gland.17,18

In the final stage, “autoreactive” T cells, B cells, and antibodies cause a massive destruction of the thyrocytes. In addition to cell-mediated immune mechanisms, HT is characterized by the production of antibodies against a variety of thyroid-specific antigens, such as thyroglobulin (TG) and peroxidase (TPO), but also the TSH receptor, sodium/iodine (NIS) symporter,19 and pendrin has been recently reported.20

Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis Disease Associations

HT in childhood and adolescence may appear combined with specific autoimmune diseases, namely autoimmune polyglandular syndrome (APS) 1 and 2 (see Table 1). APS-1, which is presented in the first decade of life, is caused by a mutation of a single gene (autosomal recessive defect in AIRE gene mapped to 21q22.3) and is characterized by the development of sequential mucocutaneous candidiasis, hypoparathyroidism, adrenal deficiency, and HT.21 APS-2 tends to occur in the period of later childhood or adolescence, with Addison’s disease in association with HT (Schmidt’s syndrome) or AIT with DM1 (Carpenter syndrome).22 Patients with a particular human leukocyte antigen genotype (HLA-DQ2, HLA-DQ8, and HLA-DR4) are at a higher risk for developing APS-2. The HT was also described in children with immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked syndrome (IPEX syndrome), a polyglandular alteration characterized by early onset diabetes and colitis, linked to the dysfunction of the transcription factor FOXP3.23 HT can coexist with other organ-specific autoimmune diseases, particularly diabetes mellitus type 1. There is a greater incidence of HT in patients with certain chromosomal alterations such as Down syndrome,24 Turner syndrome,25 and Klinefelter syndrome. The AITD may also be associated with chronic urticaria26 and, rarely, glomerulonephritis.27

Clinical Manifestations

Thyroid hormones play an important role in childhood growth and are involved in the maturation and metabolism of certain organs such as the skeleton and brain where they influence the process of myelination of the nervous system.28 One of the biggest differences between HT presentation in childhood and adults remains in the fact that HT hypothyroidism may lead to short stature, decline in school performance, and retardation of development, which have effects in adult life.29 Weak linear growth without apparent cause is a classic initial finding in many children with hypothyroidism. Short stature, with a tendency for overweight becomes evident after months or years of hypothyroidism. The majority are teenagers, clinically euthyroid and asymptomatic, but many present hypothyroidism symptoms and others, despite clinically euthyroid, have laboratorial evidence of hypothyroidism.

Typically, autoimmune thyroiditis is diagnosed in euthyroid patients based on the presence of autoantibodies, goiter or a progressive deficiency in thyroid hormones production and hypothyroidism’s symptoms. Rarely, patients may experience pain in the thyroid region, as well as compression of the trachea or esophagus. Some patients may present multinodular goiter or more rarely, may present an isolated nodule. Usually it is not associated with cervical lymphadenopathy.

In cases of thyroiditis associated with fibrotic gland, teenagers may show a short stature, decreased growth rate, or delayed bone age despite goiter absence.30 The clinical picture of HT in the adolescent population usually has an insidious presentation. In childhood, HT presents with goiter, symmetrical and painless (present in about two-thirds of all cases) or changes of growth. The clinical manifestations of hypothyroidism in adults are lethargy, cold intolerance, constipation, dry hair and/or periorbital edema. The children and adolescents with hypothyroidism tend to have a delayed puberty, but may also induce pseudoprecocious puberty, manifested as testicular enlargement in boys, breast development, and/or vaginal bleeding in girls. This syndrome clinically differs from true precocity by the absence of accelerated bone maturation and linear growth.31 Males normally have an increased testicular volume and rising levels of prolactin and TSH. Several authors consider the possibility of association between pseudopuberty and hypothyroidism due to cross-reactivity between high TSH and FSH receptors.32 The female adolescent may experience an associated precocious puberty and/or polycystic ovaries.33 Some adolescents may have clinical manifestations characteristic of hyperthyroidism such as nervousness, irritability, sweating, behavioral hyperactivity, without laboratory evidence of hyperthyroidism.34

Diagnosis

The determination of serum TSH concentration is the best screening test for primary hypothyroidism. If the TSH is high, the assessment of the serum free thyroxine (fT4) concentration will tell if the child has subclinical hypothyroidism (normal fT4) or hypothyroidism (low fT4). Diagnosis also includes positivity for anti-TPO autoantibodies and/or anti- Tg autoantibodies, accompanied by alteration of thyroid gland and clinical data of thyroid gland volume or sonographic changes of glandular structure.

Echographically thyroid gland presents a heterogeneous and hypoechogenic pattern. The hypoecogenicity is correlated with the intensity of lymphocytic infiltration, levels of circulating antibodies and the severity of hypothyroidism.35,36

Treatment

Most patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis are asymptomatic. The replacement hormone therapy is recommended for all patients with TSH

values >10 IU/mL or with TSH values >5 IU/mL in combination with goiter or thyroid autoantibodies.36 In patients with AIT-induced hypothyroidism need an average dose of 1.5 μg/kg per day (≥6 to <10 years: 2.0 μg T4/ kg per day; ≥10 to <12 years: 1.6 μg T4/kg per day; ≥12 to <14 years: 1.5 μg T4/kg per day; ≥14 years: 1.4 μg T4/kg per day). Oral administration of levothyroxine (2–4 μg/kg/day) once daily is a therapeutic option. The normalization of TSH (0.5–2 microIU/mL) is the aim of replacement therapy. Thyroid function tests should be obtained every 6–8 weeks to stabilize the TSH value within the desired range.31 The levothyroxine doses may need to be adjusted depending on the laboratory variations, in order to avoid the onset of symptoms of overdose as agitation, insomnia, flushing, diarrhoea, sweating, or tachycardia.33 Since the biochemical euthyroid status is reached, TSH should be monitored every 4–6 months in children and adolescents.

Levothyroxine should be administered at least 20 minutes before eating or drinking any medication, since it interferes with the absorption of calcium and iron as well as the potassium exchange, aluminium-containing antiacids, bile acid resins linker.

Surgical therapy (thyroidectomy) is recommended only in cases of suspected malignancy coexistence or to relieve compressive symptoms (dysphagia, cough, dyspnea, hoarseness) in patients with large goiters.37

The treatment of children and adolescents with subclinical hypothyroidism (normal fT4, high TSH) is controversial. The long-term follow-up studies of children with subclinical hypothyroidism due to AIT suggested a significant likelihood of remission. Consequently, if there is a strong family history of hypothyroidism and if the patient is not symptomatic, a reasonable option is to re-evaluate thyroid function every 6 months.

Conclusion

Adolescents who display thyroid enlargement should always be evaluated for HT and thyroid function. Although most children with HT remain euthyroid during their lives, thyroid function should be monitored periodically for early detection and treatment hypothyroidism.