The purpose of life is to reproduce. One purpose of physicians is to make

sure this happens safely. In the developed world this has been pretty

successful. And so we do not want to spoil things: we just want the results

to continue improving and to involve more countries in such success.

We certainly do not want an old-fashioned thing like thyroid disease to

interfere. And so it should not.

Women with thyroid failure can be treated easily with thyroxine

replacement therapy and as long as the mother takes sufficient

thyroxine during pregnancy the baby will be normal. If she does not

take her tablets she will most likely have a dull child or worse.1,2 Not a

good outcome but entirely preventable. The physician needs to verify

that the thyroid is being replaced appropriately and must not just trust

the mother. Trust and verify. But what about an overactive thyroid? Now

that is more of a problem and usually needs an endocrinologist to be

involved with the obstetrician. Hyperthyroid Graves’ disease is most

common in the reproductive age group and although fertility is said to

be reduced by hyperthyroidism, the data supporting this assumption

for mild disease are relatively weak. Clearly, overt hyperthyroidism will

disrupt ovulation but the more common mild degree of hyperthyroidism

is much less likely to do so and it has been estimated that the incidence

of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy is about one in 20, which seems much

too high.3

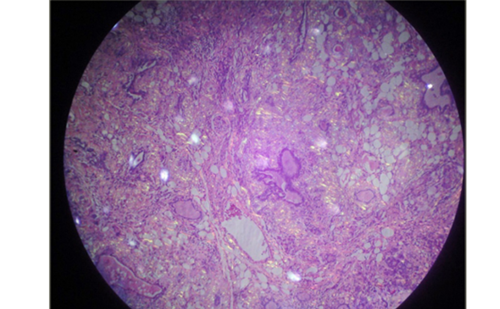

Nevertheless, plenty of women with mild disease do become

pregnant and need treatment. They need treatment because their risk for

complications is increased. Hyperthyroidism in pregnancy is associated

with increased pre-eclampsia, preterm birth, and need for induction

as well as more rare outcomes,4

and the neonates more often require

intensive care.5

These increased risks appear not to be just the influence

of excess thyroid hormone on the mother but also by the direct effects of

thyroid hormone on the fetus. This has been shown elegantly in mothers

with thyroid hormone resistance but a normal fetus6

where growth was

restricted and there was an increased risk for pregnancy loss. In addition,

in early pregnancy there may be an exaggeration of the hyperthyroidism

because of the influence of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) acting

as a thyroid stimulator.7

Treatment is, therefore, usually considered to be

needed for most women who are pregnant with hyperthyroidism.

So how to do this? The treatment of hyperthyroidism has not changed for

more than 50 years. We may be better informed and better able to use the

same old treatments but there has not been a fundamental shift in the

approach. It remains antithyroid drugs, radioiodine and surgery. Each has

well-known advantages and disadvantages and the informed young women

does not like any of them. And right she is. What a terrible choice to have

to make when carrying a precious child. Radioiodine is out straightaway for

obvious reasons. Surgery, the original treatment for Graves’ disease is never

anything to rush into unless you are a surgeon. That leaves antithyroid drugs.

Or does it? Let us first deal with antithyroid drugs. The US Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) has now black boxed propylthiouracil (PTU) because

of the unacceptable increased risk for liver failure, especially in children;8

therefore, its use as first-line treatment is no longer recommended.9

The

first drug of choice is now methimazole. But methimazole in pregnancy has

been well established to cause what has become known as a methimazole

embryopathy (see Table 1)

10 and potentially involves many different tissues.

So the thyroid community came up with the suggestion to switch to PTU

for the first trimester of pregnancy and then to switch back to methimazole

after organ formation is completed.9

This scenario assumes that you see the patient in early pregnancy. But that

is unlikely to be before 6 weeks—after a good deal of human development

has taken place. In essence, using this approach requires a switch to PTU

at 6 weeks and then a return to methimazole at 12 weeks with barely time

to even determine the correct dose. A better way is to switch antithyroid

drugs when the woman is planning a pregnancy although this ignores the

matter of unexpected pregnancies. If this approach does not sound difficult

enough, who says PTU is safe? There are good experimental data showing the

teratogenic effects of PTU11 and recently Peter Laurberg’s group in Denmark

have shown that there are PTU-associated birth defects in the face, neck, and

urinary system after PTU exposure.12 These tended to be less severe than after

methimazole but still mostly required surgical correction. In my view that ends

the recommended logic. Clearly neither antithyroid drug is a great choice.

So are there more options for the treatment of hyperthyroidism in

pregnancy? There are in fact two other choices. The first is not to get

pregnant. But of course it may be too late for that approach. But it is the

advice that should be offered to those young women already diagnosed

with hyperthyroidism. Delay until you are appropriately treated. And

if you are in a hurry? Or if your eggs are aging? Then go ahead and

have surgery. It is now safer than ever before if you go to a high volume

thyroid surgeon.

The second extra choice is to do nothing. If the disease is mild, the

chance of major complications is small and as the immune suppression

of pregnancy develops in the second trimester the disease will almost

certainly dissipate.13 But physicians are really bad at doing nothing.

Get used to it.